El mundo sanitario en general y la medicina de familia, que vivo en primera persona, en particular atraviesan un desierto. Eso implica pasar sed, mucho calor y caminar despacio. Lo peor que te puede pasar en el desierto es vagar perdido. No saber dónde estás y no saber a dónde ir, además de ser un castigo es una condena de muerte. Nadie aguanta mucho tiempo en un desierto. Los que sobreviven en él aprenden a entrar y salir, a atravesarlo saltando de oasis en oasis, pero no es posible caminar 40 años por sus dunas por más que lo diga el Pentateuco.

Por eso creo necesario descansar un momento de la narrativa distópica y quejosa predominante y adentrarnos en la ciencia ficción utópica capaz de diseñar escenarios de vida y supervivencia. Esto implicará usar la imaginación y nos dará los grados de libertad suficientes como para poder marcarnos una vía de salida sabiendo que hay posibilidades de mejora en algún lugar futuro. Tengo claro que solo alcanzaremos una nueva narrativa profesional si se genera una ebullición de ideas colectivas con esta base que nos ayuden a empezar a caminar hacia horizontes de valores éticos, salud comunitaria, educación para la salud, autonomía del paciente, consultoría longitudinal, trabajo en equipos reales, autonomía de gestión y todos aquellos puntos de luz que queramos poner en nuestros horizontes.

Y en cuanto al nuevo marco teórico habría que repasar la trinidad de verbos principales para dar un repaso a nuestra identidad. Empezaríamos con el verbo SER que nos devuelve la pregunta clásica ¿Quién soy yo profesionalmente? Y nos obligará a mirar todo lo que se nos ha ido pegando a la piel más allá de una bata. Encontraremos roles profesionales diversos, ejemplos de otros colegas significativos, las consabidas películas y series médicas que pueblan nuestros subconscientes colectivos, las ventajas de un trabajo para siempre… y todo aquello que ustedes descubran. Si somos honrados también descubriremos mucha sangre dado que somos salientes de Pandemia y sin duda nos habrá salpicado o tendremos alguna herida abierta que aportar. Una vez examinado el cuerpo del asunto con visión técnica, propondría una contemplación del mismo en clave compasiva. Somos sanadores heridos y hacer presente nuestro dolor es la clave de bóveda para poder sostener el ajeno, esto se nos olvida con frecuencia porque nos resulta aparentemente más ventajoso esconder lo duro de la vida en el armario, que es precisamente lo que hacen todos nuestros pacientes. Poca ayuda podremos aportar sin salir de nuestro propio armario, sin abrirlo.

Pero antes de contar cómo conseguirlo será acertado detenernos en el verbo ESTAR que es profundamente revolucionario. Permanecer en el puesto realizando la misión encomendada es hoy casi una heroicidad, sobre todo cuando hay cuatro compañeros de baja y la sobrecarga de pacientes es mayúscula, ustedes ya me entienden. Estar significa no irse, no escapar. En muchos momentos se nos antoja casi imposible. Cada semana vemos más compañeros que se van, que no aguantan más, que lo dejan. Y notamos con miedo como hay otros muchos que se lo piensan, un miedo intenso a que nos dejen solos, con lo que eso significa. Pero pese a todo, sigue habiendo profesionales que deciden estar, permanecer, seguir estando. Quiero manifestarles mi admiración y agradecimiento porque sin quererlo son faros para muchos que vagamos perdidos. Comparten una luz que ayuda a situarse, a saber dónde empieza la tierra y dónde el mar, que nos recuerdan que es posible seguir navegando. Y los pacientes y comunidades agradecen cada vez más que también ellos tengan estos faros que alumbran en la noche, una noche cada vez más llena de luces de colores que no ofrecen verdadera respuesta a sus problemas.

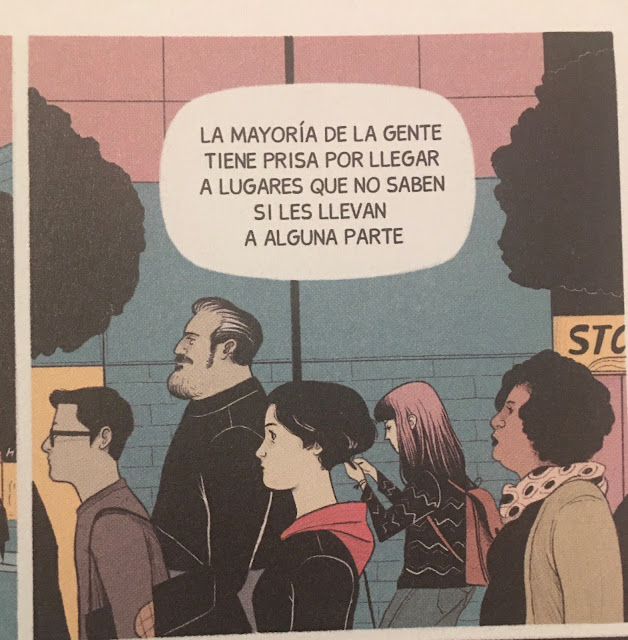

Y terminaremos el viaje con el tercer verbo elegido: HACER. Y me dirán que nos pasamos el día haciendo y es verdad, hacemos mucho, hacemos de más, hacemos demasiado. Eso nos condena a un permanente agotamiento que compartimos con el resto de una ciudadanía obligada a producir cada vez más deprisa. Por eso se tolera cada vez peor todo aquello que nos resta velocidad. Un pequeño catarro, una pequeña molestia, nos hace menos competitivos, nos frena, nos limita. Entramos en pánico cuando un niño amanece con fiebre pensando en el operativo que nos tocará montar los siguientes días. O cuando amanecemos con dolor de cabeza o con una molestia en la espalda tras jugar al Pádel en mala forma física. Los médicos sabemos dónde terminan muchas de estas situaciones que antiguamente se solucionaba cada cual dándose tan solo un poco de tiempo, tiempo que hoy vale mucho dinero. En lo que significa ser médico en esta época diremos que el hacer se ha multiplicado hasta el límite. No nos es posible ver más pacientes, diagnosticar más cuestiones, aplicar más tratamientos. Los gerentes sanitarios nos azuzan para aumentar la producción pero no es posible. El sistema no da más de sí por pura limitación de sus profesionales. Quizá se podría mejorar la eficiencia con una gestión basada en valores humanos, pero con la actual basada en resultados no conseguirán más. Ahora bien, ¿dónde poner la palanca del cambio para levantar la situación?. ¿Dónde apostar para HACER lo verdaderamente importante? Si tuviéramos solo una palanca yo propondría apoyarla en la relación médico paciente, el corazón del sistema sanitario. Esto nos obligaría a modificar el hacer para centrarlo en lo que ayude a potenciar esa relación, en lo que aporte tiempo y energía para que sea esa relación la que favorezca que el paciente pueda lidiar con sus problemas tanto de salud como de la vida ordinaria, a la vez que favorezca que el profesional pueda detectar la enfermedad y sea operativo en las cuestiones solucionables.

Me dirán que en la teoría queda bonito pero faltan claves para implementarlo y aceptaré la crítica. No esperen que nadie les dé esas claves, por muy dulce que sea el discurso o por mucho que utilicen la palabra innovación, les estarán vendiendo humo. Les va a tocar hacer un viaje personal por los tres verbos y ser ustedes quienes los conjuguen con lo que vean que son, con lo que sean capaces de estar, o con lo que puedan hacer o dejar de hacer. Les invito a mirarse en profundidad, deteniéndose especialmente en sus armarios y heridas. Dense el tiempo necesario para ello, pueden llegar a necesitar meses. Luego, más tarde, ya podrán empezar a mirar a otros, que los hay. Gente buena que es faro y emite luz de forma generosa. Abran los ojos y atrévanse a mirar a otras categorías profesionales, incluso fuera de lo estrictamente sanitario. Hay pacientes, grupos, asociaciones, profesionales que trabajan en las comunidades, voluntarios… haciendo cosas maravillosas.

Como ven es posible generar una narrativa sanitaria distinta, y lo que es mejor, dar un primer paso. Efectivamente seguiremos visibilizando cómo está la situación y reconociendo las cosas como son, pero nadie nos puede quitar la opción de imaginar futuros más brillantes o de imaginar las primaveras por venir.

Towards a new narrative

The world of healthcare in general and family medicine, which I experience first-hand, in particular, is a desert. That means being thirsty, very hot and walking slowly. The worst thing that can happen in the desert is to wander around lost. Not knowing where you are and not knowing where to go is not only a punishment but also a death sentence. No one can last long in a desert. Those who survive in it learn to get in and out, to cross it by jumping from oasis to oasis, but it is not possible to walk 40 years in its dunes, no matter how much the Pentateuch says so.

This is why I believe it is necessary to take a break from the predominant dystopian and complaining narrative and enter into utopian science fiction capable of designing scenarios of life and survival. This will involve using our imagination and will give us sufficient degrees of freedom to be able to chart a way out knowing that there are possibilities for improvement somewhere in the future. It is clear to me that we will only reach a new professional narrative if we generate a boiling up of collective ideas with this base that will help us to start walking towards horizons of ethical values, community health, health education, patient autonomy, longitudinal consultancy, work in real teams, management autonomy and all those points of light that we want to put on our horizons.

As for the new theoretical framework, we should review the trinity of main verbs in order to review our identity. We would start with the verb TO BE, which brings us back to the classic question: Who am I professionally? And it will force us to look at everything that has become attached to our skin beyond a dressing gown. We will find diverse professional roles, examples of other significant colleagues, the well-known films and medical series that populate our collective subconscious, the advantages of a job forever... and whatever else you discover. If we are honest, we will also discover a lot of blood, as we are Pandemic's progenitors and will no doubt have been splashed or have some open wounds to contribute. Having examined the body of the issue with a technical vision, I would propose to contemplate it in a compassionate way. We are wounded healers and making our own pain present is the key to being able to sustain the pain of others. We often forget this because it is apparently more advantageous to hide the harshness of life in the wardrobe, which is precisely what all our patients do. We can do little to help without coming out of our own cupboard, without opening it.

But before telling how to achieve this, it would be wise to dwell on the verb STAY, which is profoundly revolutionary. Staying on the job and carrying out the mission entrusted to us is today almost a heroic deed, especially when there are four colleagues on sick leave and the overload of patients is enormous, if you know what I mean. Being there means not leaving, not escaping. At many times it seems almost impossible. Every week we see more and more colleagues who leave, who can't take it any more, who quit. And we notice with fear how many others are thinking about it, an intense fear of being left alone, with what that means. But in spite of everything, there are still professionals who decide to stay, to remain, to continue to be. I want to express my admiration and gratitude to them because they are unwittingly beacons for many of us who are wandering around lost. They share a light that helps us to find our bearings, to know where the land begins and where the sea begins, that remind us that it is possible to continue sailing. And patients and communities are increasingly grateful that they too have these beacons to shine in the night, a night increasingly filled with coloured lights that offer no real answers to their problems.

And we will end our journey with the third verb chosen: DOING. And they will tell me that we spend the day doing, and it is true, we do a lot, we do too much, we do too much. This condemns us to a permanent exhaustion that we share with the rest of a citizenry forced to produce faster and faster. That is why everything that slows us down is tolerated more and more. A little cold, a little discomfort, makes us less competitive, slows us down, limits us. We panic when a child wakes up with a fever, thinking about the operation we will have to mount the following days. Or when we wake up with a headache or a sore back after playing padel in bad physical shape. As doctors we know where many of these situations end up, which in the past could be solved with a little time, time that today is worth a lot of money. In terms of what it means to be a doctor in this day and age, we would say that the workload has multiplied to the limit. We can no longer see more patients, diagnose more issues, apply more treatments. Health managers encourage us to increase production, but it is not possible. The system can only cope with so much because of the limitations of its professionals. Perhaps efficiency could be improved with a management based on human values, but with the current one based on results they will not achieve more. But where to put the lever of change to lift the situation, where to bet on DOING what is really important? If we had only one lever, I would suggest supporting it in the doctor-patient relationship, the heart of the health system. This would force us to modify what we do to focus on what helps to strengthen this relationship, on what provides time and energy so that it is this relationship that helps the patient to deal with their health problems as well as ordinary life problems, while at the same time helping the professional to detect illness and be operative in resolvable issues.

You will tell me that in theory it looks nice but there are no keys to implement it and I will accept the criticism. Don't expect anyone to give you those keys, no matter how sweet the discourse or how much they use the word innovation, they will be selling you smoke. You will have to make a personal journey through the three verbs and be the ones to conjugate them with what you see you are, with what you are capable of being, or with what you can do or not do. I invite you to take a deep look at yourself, looking especially at your wardrobes and wounds. Give yourselves time to do this, it may take months. Then, later on, you can start looking at others, and there are others. Good people who are lighthouses and give off light in a generous way. Open your eyes and dare to look at other professional categories, even outside the strictly health sector. There are patients, groups, associations, professionals working in communities, volunteers... doing wonderful things.

As you can see, it is possible to generate a different health narrative, and even better, to take a first step. Indeed, we will continue to make the situation visible and recognise things as they are, but no one can take away the option of imagining brighter futures or imagining the springs to come.

迈向新的叙述方式

机器翻译,抱歉有错误。

一般来说,医疗保健的世界,特别是我亲身经历的家庭医学,是一个沙漠。这意味着口渴,非常热,走路很慢。在沙漠中可能发生的最糟糕的事情是迷失方向的徘徊。不知道自己在哪里,不知道去哪里,不仅是一种惩罚,也是一种死刑。没有人能够在沙漠中坚持很长时间。在其中生存的人学会了进出,通过从绿洲跳到绿洲来穿越它,但不可能在它的沙丘上走40年,无论摩西五经怎么说都是如此。

这就是为什么我认为有必要从占主导地位的歇斯底里和抱怨的叙述中抽身出来,进入能够设计生活和生存场景的乌托邦式的科幻小说。这将涉及到发挥我们的想象力,并将给我们足够的自由度,使我们能够在知道未来某个地方有改进的可能性的情况下规划出一条出路。我很清楚,只有当我们在这个基础上产生了沸腾的集体想法,帮助我们开始走向道德价值、社区卫生、健康教育、病人自主、纵向咨询、真正的团队工作、管理自主和所有我们想放在视野中的光点,我们才能达到一个新的专业叙述。

至于新的理论框架,我们应该回顾三位一体的主要动词,以审查我们的身份。我们会从动词TO BE开始,这让我们回到经典的问题:我在职业上是谁?而且,它将迫使我们审视已经附着在我们的皮肤上的一切,而不仅仅是一件睡衣。我们会发现多样化的职业角色,其他重要同事的例子,充斥着我们集体潜意识的知名电影和医疗系列,永远的工作优势......以及其他你发现的东西。如果我们是诚实的,我们也会发现很多血,因为我们是大流行的祖先,无疑会被溅到,或者有一些开放的伤口贡献。在以技术眼光审视了这个问题的主体之后,我建议以一种同情的方式来思考它。我们是受伤的治疗者,让我们自己的痛苦呈现出来是能够维持他人痛苦的关键。 我们经常忘记这一点,因为把生活的严酷性隐藏在衣柜里显然更有利,这正是我们所有病人的做法。如果不从我们自己的柜子里出来,不打开柜子,我们能做的帮助很少。

但在讲述如何实现这一目标之前,最好先说说STAY这个动词,它具有深刻的革命性意义。今天,坚守工作岗位,执行委托给我们的任务几乎是英雄式的,尤其是在有四位同事请病假,病人超负荷工作的情况下,如果你明白我的意思。在那里意味着不离开,不逃避。在许多时候,这似乎几乎是不可能的。每周我们都会看到越来越多的同事离开,他们不能再忍受了,他们辞职了。我们恐惧地注意到有多少人在思考这个问题,一种强烈的恐惧,害怕被抛弃,害怕这意味着什么。但尽管如此,仍有专业人员决定留下来,继续留在那里,继续存在。我想向他们表示钦佩和感谢,因为他们在不知不觉中成为我们许多迷茫徘徊的人的灯塔。他们共享一束光,帮助我们找到方向,知道陆地从哪里开始,海洋从哪里开始,提醒我们有可能继续航行。病人和社区越来越感激他们也有这些灯塔在黑夜中闪耀,这个黑夜中越来越多的彩色灯光,没有为他们的问题提供真正的答案。